A note from Siofra

Hello my dear folklore friends!

Firstly an apology, I made a bit of a mistake with the recording of our September talk by Darren Mann from the Paranormal Database. I placed the recorder right next to the projector so all you can hear is an annoying buzz all the way through. Lesson learned.

It’s such a shame because Darren’s talk was brilliant. If you would like to listen to Darren, you can find him hosting a weekly radio show (Sunday 10am-12pm) called WSH: Beyond Breakfast on Ipswich Community Radio.

Tickets for our next talk sold out in 8 hours, so thank you to everyone who snapped one up. If you did manage to get a ticket, don’t forget we’ll be having a book swap after the talk. Ideally books have a suitably folklore/supernatural/magical etc theme.

October is turning out to be as busy as ever for us. October 1 saw the launch of our website and our Halloween countdown. It feels really good to have a proper home for all our stories. If you haven’t visited yet, do pop on over for a look (HERE). We have four excellent stories on there at the moment and once the Halloween countdown has finished we will be regularly adding more of our collection.

I hope you’ve been enjoying the Halloween countdown on the old social media. Stacia has been squirreling away little spooky treats for you all year and I had fun doodling some covers for each story.

We have a few events lined up this month and it would be lovely to see some familiar faces. If you are reading this on October 15, then the still might be time to come along to Gressenhall Apple Day. We’ll be in the cottage kitchen to talk to visitors about the folklore & magic of apples and local folklore. Stacia has mentioned a couple of other bits we are are up to.

I’ll also be at Norwich Pagan Moot’s Boudica’s Brocante on Sunday 29 October with my Shuck Zine hat on. It really is a brilliant little fair selling all kinds of magical items, and the Ickney might be there! Details of the fair are HERE.

And finally, we have our next talk coming up in the undercroft of the Louis Marchesi. We are really looking forward to seeing how this venue works for us. It’s obviously not quite as atmospheric and cosy as Arboretum, but being underground should be fun. If you managed to get tickets, we are going to have a book swap after the talk.

Well, I think that’s it for now. I’m almost looking forward to November so I can have a rest…

Siofra 💚

A note from Stacia

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! It’s been a busy work-month (while we all know that the weird path isn’t just for Halloween, it’s for life, the rest of the world goes into overdrive for October) and I have been tethered to my office writing my fingers to the bone in preparation. Talk about ghost writing…

We’re in the middle of our Halloween Advent Calendar on our social pages and website, we’re working on some incredibly exciting projects in the future, we’ve got talks and events planned, we’re at the Elizabethan Museum in Great Yarmouth’s Witch Craft Day on October 25 talking about all things witchy and today, Siofra and I are due to be at Gressenhall Farm and workhouse TODAY talking about apple lore in the Victorian kitchen for a few hours for its annual Apple Day celebrations.

We’ve also worked with Gressenhall to create a special Norfolk Folklore Society Trail which encourages visitors to seek out some exbibits or areas that link to lore – it’ll be available throughout half-term as a sheet you can follow and we’ll also be including it on our website.

Finally, a thank you to Siofra who has worked SO HARD on putting together our wonderful new website which will give all our stories a home. We’ll be linking to them from our social sites and it means more content, more photographs and more chances to take back our rightful crowns as Queens of the Weird in Norfolk after what has been a…testing…year in terms of having a proper home online. Please, please share what we do with anyone you think will love what we do and if you have your own stories, get in touch. We are dedicated to protecting Norfolk folklore, and that from further afield, and documenting the stories found by us and told to us for the generations to follow. No paywalls, no pop-ups, just a shared love of the weird in Norfolk.

Happy Halloween to you all,

Love, Stacia

Nutcrack Night

Halloween is a liminal time when the veil between the worlds – our world and the Shadowlands – is very thin. It is a time for departed spirits to return with messages for loved ones and a time for divination, for the ghosts of the past to help people face the future.

Another name for Halloween (particularly, according to some stories, in the Brecks) was Nutcrack Night: hazelnuts would be given the names of potential suitors and set by the fire.

The first nut to jump and crack would give a young woman the name of her husband-to-be. If only one suitor had claim to her heart, a single nut would be named and tested with the words: “If you love me, jump and fly, if you hate me, lie and die.”

The shapeshifting horror of The Hateful Thing in Geldeston

As befits one of the wildest areas of the county and in the midst of marshland, The Hateful Thing waits in the darkness for unsuspecting passers-by.

The Norfolk Folklore Society only recently interviewed eye-witnesses to something terrifying in these waterlogged lands (listen HERE) but It has been catalogued for centuries.

Geldeston is on the border of Norfolk and Suffolk, on the north bank of the River Waveney between Bungay and Beccles, named for the Geld Stone where in the 10th century, Danegeld tax was paid.

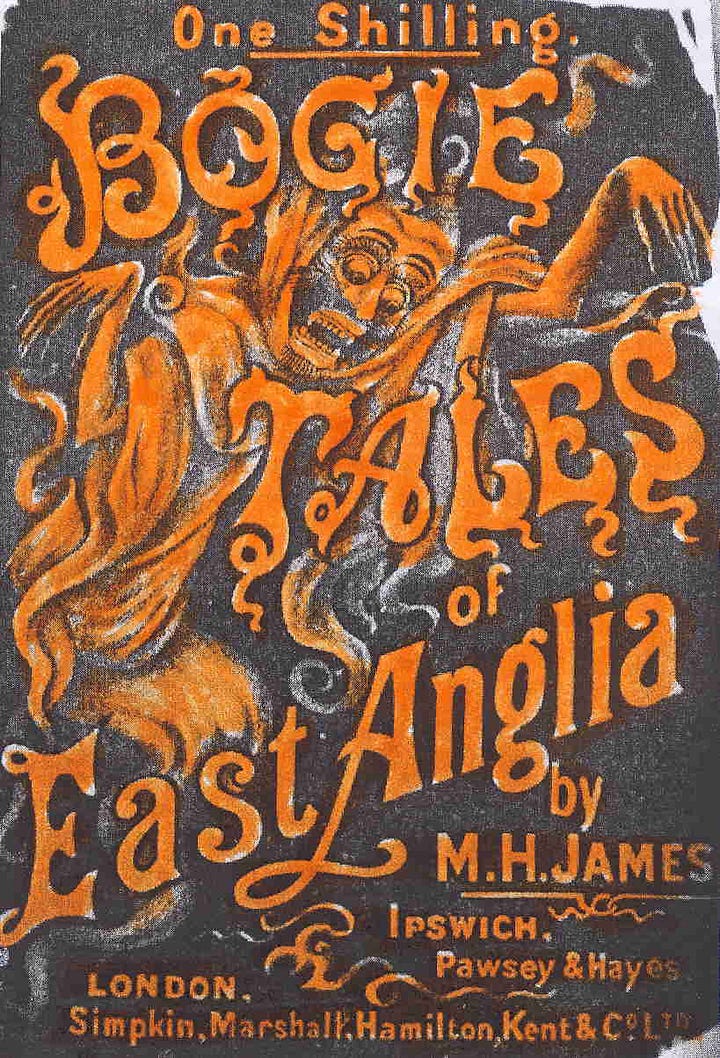

Bogie Tales of East Anglia was written by Margaret Helen James in 1891, a remarkable woman and one of the first to devote an entire book to East Anglian folklore. Margaret grew up with ghost stories.

Her first cousin Montague Rhodes James’ nightmares and visions in Suffolk - where she too was raised – led to him penning chilling tales such as The Ash Tree, A Warning to the Curious and Oh, Whistle and I'll Come to You, My Lad.

James was a regular visitor to Great Livermere, where her uncle was rector and where her cousin MR James lived from the age of three. It was there he saw a Hateful Thing of his own, an unimaginable horror that lay in wait in the darkness and crept towards him when he blinked.

Pink, malevolent and with large open eyes, the creature peered at him from a hole in the garden gate before shambling away into the trees. Horror, folktales, fear and dread ran through the veins of the James family.

In her book, Margaret writes of “an uncomfortable sort of ghostly terror, in beast form, that haunts villages on the borders of the two counties [Norfolk and Suffolk] which is commonly called the ‘Hateful Thing’.

“I allude to the churchyard or hell-beast. This charming creature generally takes the somewhat indefinite form of a ‘swoundling’, ie swooning shadow. Whenever it is met in any locality, it is a sign that some great and unusually horrible wickedness is about to be committed, or has just taken place there.”

A ‘swoundling’ is something which would produce a swoon, something so hideous, so heinous, so other-worldly that it overrides the human instinct of flight and instead causes the heart to slow, pump less blood and the body to fall where it stands. It stands to reason that such a sight might very well be a Hateful Thing.

Church beasts, or Grims, are guardian spirits in English and Nordic folklore that watch over churches and churchyards, protecting both from those who mean them harm. In England, the Church Grim is most often seen as a large black dog which offers protection from not only thieves and vandals, but more powerful forces such as witches, warlocks and the Devil.

The belief that the first soul to be buried in a new churchyard would spend eternity protecting it led to a ritual which saw animals, usually dogs or boars, being buried at the cornerstone of a church as it was built. A foundation sacrifice meant no human would be press-ganged into an endless role as caretaker in the afterlife, instead leaving creatures anchored to Earth-bound tasks for eternity.

If the Grim was ever seen by human eyes, it was an ominous portent, and if it rang the church bell at midnight, death would quickly follow.

During funeral services, if the clergy taking the ceremony spied the Grim as the body was being lowered into the ground, it was said they could tell whether a soul was heaven or hell-bound by the way it looked back at them.

Some tales claimed that if you were the last to die during the year, your fate would be to serve the Church Grim for the following 12 months, others that the Grim was, rather than a guardian, an evil parasite drawn to the energy of the church where it could hungrily feed on people’s dreams, hopes and fears.

Margaret wrote: “…the Church Beast was driven over the threshold of every new Church by the devout Norse colonisers here, as in their own land, in order that the Devil, who claimed the first living thing that entered a church, might be satisfactorily compounded with.

“The beast was then walled up in the building, and was supposed to issue forth on nights of omen, or before great events, and to hobble through the township, stopping and howling after its kind before the house where Death stood on the threshold.”

At the beginning of her tale, Margaret mentions a close encounter she had with the Hateful Thing: “The writer, when crossing a field at night, once came on a countryman who had just seen this apparition, but a slight search for the goblin was wholly unsuccessful.”

She continues with a “…carefully authenticated story, from a host of others on the same subject…” which is “…given in the words of the narrator...

“Mrs S tells her story as follows: “My youngest daughter, A, was keeping company with a young man…So A, she says to me, ‘Mother’, she say, ‘a walk in the evening’d do you good, do you come along of us’. I went along, together, as they seemed to want me - unusual daughter! – and A and the young man took me to Gillingham, and then, about eight or nine, we came back to Geldeston, over market path, and it was that time I saw the Hateful Thing.

“Just as we got over the stile, into the road, A say ‘Mother’, she says, ‘how that dog did frighten me!’ I says, ‘Where?’ and neither me, nor the young man see any dog.

“’It’s on ahead’, says A, ‘and O, it ain’t a dog, it’s bigger than a horse now, and it’s walking slow.’ Now I began to get skeary, and I minded that A had been born under the chime hours, so she could see things.

“Well, A clung to her young man, and I listened, and I heard a thumping, but could see nothing. ‘Well,’ A said, ‘O, we are just agin it,’ and the young man struck with his stick about the road. Then A, she come over and cling hold of me and the moment she touched me I saw the Hateful Thing.

“The beast was black, and didn’t keep the same size, and it wasn’t any regular shape. We walked slow, for I was afraid of its getting behind us, and we kept just agin it. I lost sight of it every time A left hold of me.

“The young man wasn’t a bit afraid, he saw nothing, but he heard the thumping. Well, we went on half-a-mile, and it was terrible passing Gelders, for I had seen things there afore.

“The beast kept on afore us, till it came to the sandy lane that go up to the churchyard, and went off there, and we went up the village, and A’s young man had to go right back up the road, for he came from Beccles.”

The Gelders or Gelders Clump stands in the triangular centre of a road convergence which used to be the site of the 'Geld Stone', while the church mentioned is St Michael (St Michael boasts another dread spectre, a chilling story for another day).

In Norfolk and Suffolk, it was widely believed that if you were born in the ‘chime hours’, a term alluding to the old monastic hours of night prayer (8pm, midnight and 4am), which many rural churches marked by bell-ringing even after the Reformation, you would be able to see much that was hidden from others.

How to cure those bewitched at Halloween

“A remedy for those bewitched. Take two horseshoes, heat them red hot, and nail one on the threshold of the door, but quench the other in the urine of the party betwitched: then set the urine over the fire in a pot or pipkin, and put the horseshoe into it. Make the urine boil, with a little salt put unto it and three horseshoe nails, until it is almost all consumed: what is not boiled away, cast into the fire. Keep then your horseshoes and nails in a clean paper or cloth, and use the same manner three times. It will be the more effectual if it be done at the change or full of the Moon.”

Doctor Lilly’s Last Legacy, 1683

NFS A-Z: H is for Happisburgh Torso

Its legs severed at the knee and its head bumping along on its back attached by only a small flap of skin, the spectre drifted at a dreadful speed towards the village well.

Dressed in traditional sailors’ garb and carrying a bulging hessian sack at its chest, confused witnesses tried to make sense of the horror they saw ahead of them. Then they spotted the sailor’s pigtail grazing the ground hanging from a head that was almost, but not quite, severed, linked to the body by just a thin strip of flesh.

And then they heard the most terrible, ungodly sound, a deep, keening groan, a death rattle that followed the spectre along the street as it raced to its destination.

From the roadside, two farmers watched as the creature made its way purposefully towards a triangle of land on the edge of Happisburgh at Whimpwell Street, floating up to the brick-built well and then, after a minute or so, disappearing into its depths.

It was 1765 and the pair had seen – and heard - The Happisburgh Torso, surely Norfolk’s most gruesome ghost, the fleshy remains of a cowardly fight over smugglers’ spoils, the (almost) embodiment of what everyone dreads seeing on a dark alley.

Writing History and Legends of the Broad District in 1891, author Ernest Suffling recounted the grisly tale and reiterated the horror seen on the road in Happisburgh by the incredulous farmers in 1765.

“Although its head was reversed and turned away from the direction in which it was going, it still kept a straight course along the middle of the road until it came to the well; here it paused, and balancing its burden in its arms, dropped it endways down the mouth, and after gliding aimlessly around for a minute or two, quietly disappeared down the well also,” he wrote.

The farmers’ account to villagers the next morning must have been compelling as they managed to convince others to help them search the well. A young man called Harmer volunteered to be lowered down the well on a rope – carrying a lantern, he descended into the ground, inching down foot by foot until he was 40ft below the surface. He saw nothing untoward and signalled to be hauled back up.

As he began to move towards the light, a scrap of dark blue cloth caught his eye as the flame of his lantern illuminated the brick well – he called up to be lowered once again to search the water a second time.

With a pot hook tied to a clothes line, he fished through the water until he felt something solid caught on the hook: heaving it from the water, he saw a hessian sack, heavy and filled with something foul-smelling.

Hauled back to dry land, the sack was investigated: it contained a pair of boots with the legs of its one-time owner still inside.

A fisherman with strong sea-legs bravely returned to search for more answers once the well had been drained. He returned with the rotting body of a man whose head was almost severed, held to his body by just a single flap of skin at the back of his neck.

The corpse wore a sailor’s frock coat, and a brass-buckled belt to which was attached a pistol – shortly afterwards, close to nearby Cart Gap, a bloodstained patch of sand was found and, near it, fragments of a bottle and the glint of a gold coin or two.

It was surmised that a smugglers’ quarrel had broken out and that one of the combatants had been killed and then his legs hacked off to make carrying his body easier.

When the moon was full or before terrible storms, it was said that the same dreadful groan the farmers had heard in 1765 could be heard reverberating around the brick-lined well – it was a brave soul that went for water at night.

Do you have a story for the Norfolk Folklore Society? Email us at norfolkfolkloresociety@gmail.com

Our next podcast will be released on November 1

PS Also, about the witchcraft and witch bottles deployed as a folk practice within living memory .... Several years ago I gave a talk about magic and witchcraft in the Brecks to a variety of museum and historical society groups. It was truly amazing to witness how often an audience member would come forward afterwards to tell me shyly of something they’d witnessed as a child, or that someone they knew had found a witch bottle under their hearth during renovations.

It was great to read a slightly different version of the Happisburgh ‘ghostly smuggler’ story than the one I’d found when I was doing some writing inspired by Happisburgh cliff top, lighthouse, smugglers et al. Thank you! Just to add - I don’t think it’s mentioned here although I may have missed it - that of course the name Whimpwell (the hamlet) and Whimpwell Street derive from the wailing sounds the well is reputed to have made. That makes it all the more real, somehow, as you can see the name on the street sign to this day. And in the version of the story I found, the villagers found the rotting remains of a brandy cask under a patch of brambles at Cart Gap, where there are plenty of brambles still!